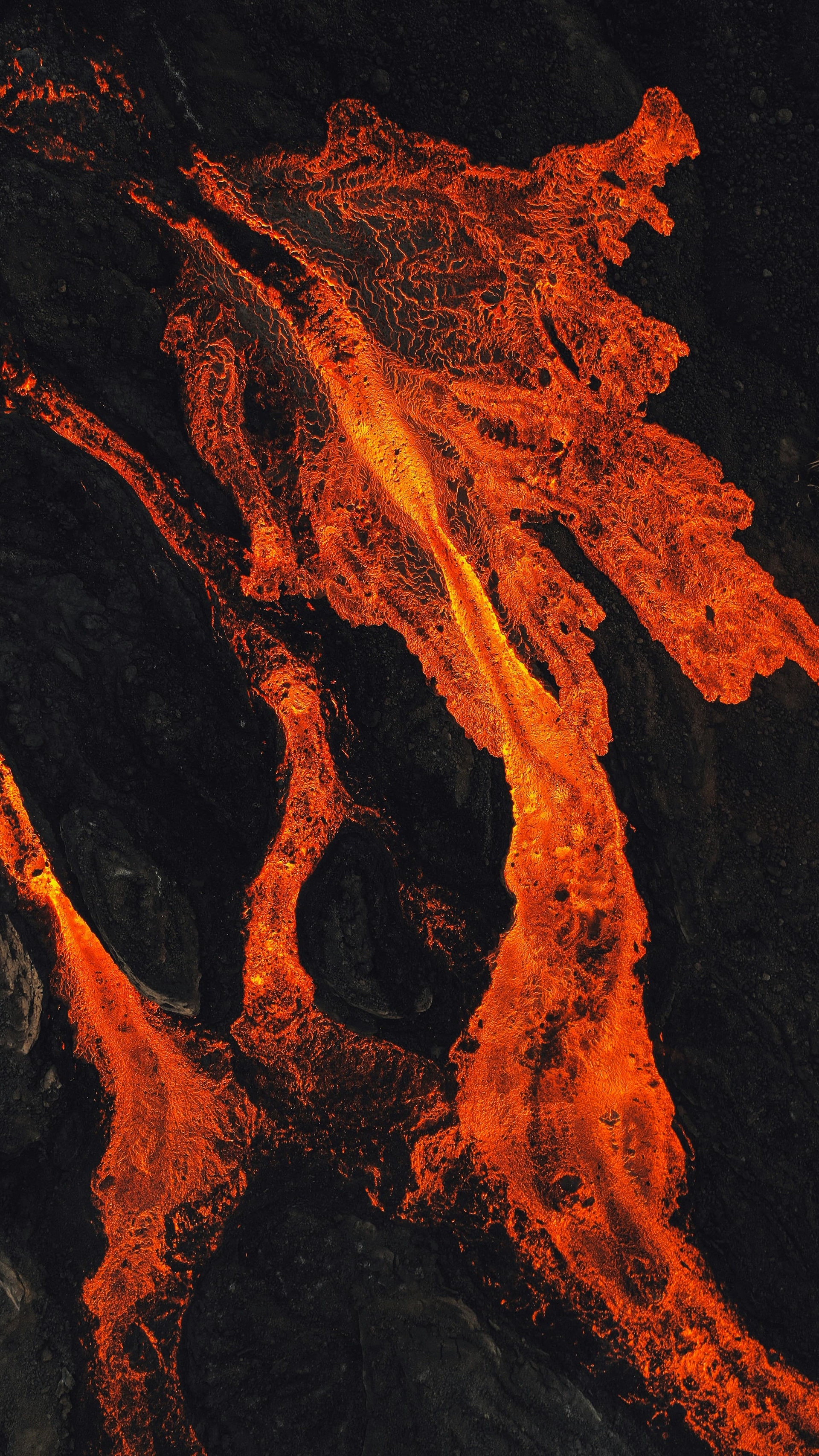

The inside of a Volcano photographed from the air

There are photographers who chase golden hours, others who chase trends—and then there are those who chase lava. The rare breed of humans who look at a 1,200°C river of molten rock and think, yeah, that would make a killer composition.

Volcano photographers are not thrill-seekers by hobby; they’re professionals whose version of “getting closer to the subject” involves gas masks, titanium tripods, and shoes melting into the crust.

Volcano photography isn’t about pretty colors or viral shots. It’s about standing on the knife’s edge between creation and destruction—capturing nature at its most violent, beautiful, and temporary.

Volcano photography isn’t about pretty colors or viral shots. It’s about standing on the knife’s edge between creation and destruction—capturing nature at its most violent, beautiful, and temporary.

The Seduction of Fire

Volcanoes are raw spectacle. They breathe, roar, and sculpt the planet. The light is unlike anything else—so brutal it rewrites your color calibration. For photographers, that intensity is addictive. Lava isn’t static; it moves, cools, bursts, and reshapes in real time. Every second offers a different frame, a different risk.Most landscape photographers wait for clouds to part. Volcano photographers wait for the mountain to explode. The payoff? Shots so unreal they make digital renders look flat. The cost? Let’s just say it’s higher than any lens insurance covers.

The Dangers Hidden in Beauty

Standing a few meters from liquid rock isn’t a metaphor. It’s lethal. The heat can kill from a distance. One step on unstable crust, and you’re gone. Toxic gases—sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide—can knock you unconscious in seconds.

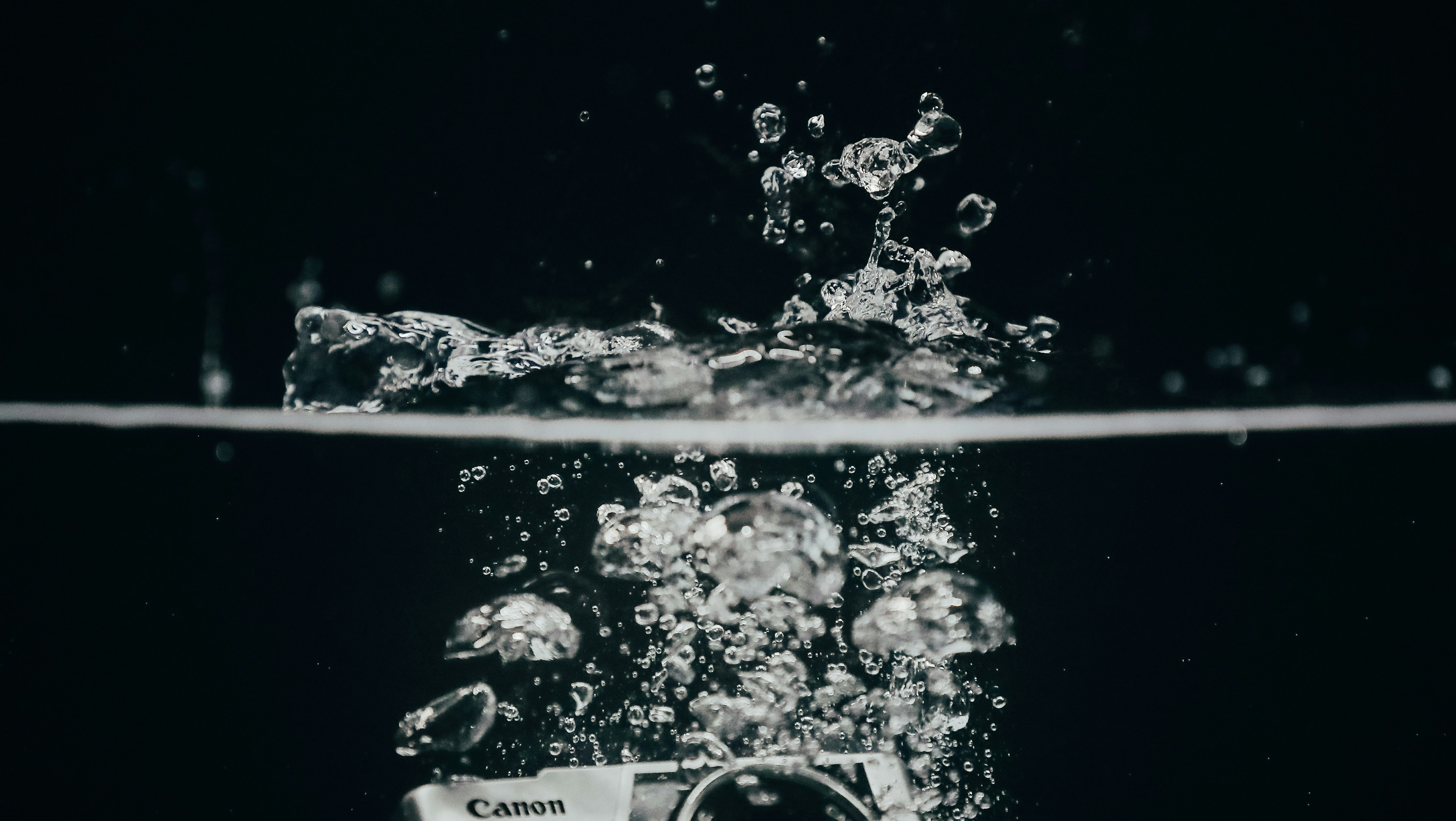

Then there’s the camera gear. Lenses fog from the heat; sensors overheat; tripods sink; drones melt midair. Photographers have watched equipment worth thousands of dollars literally liquify in front of them. The irony: the closer you get, the more the image shimmers with life—and the higher the chance you’ll never leave with it.

Professionals who document eruptions often wear heat-resistant suits and respirators, but even with full gear, the environment is unpredictable. One shift in wind direction can turn safe ground into a death zone.

And yet, they keep coming back.

The Psychology of Those Who Chase Fire

To outsiders, it looks like madness. To the photographers themselves, it’s devotion. There’s something deeply primal about documenting a volcano. It’s the planet’s heartbeat—violent, ancient, honest.

Many describe it as meditative. Amid chaos and danger, there’s a strange stillness. You can’t think about emails, deadlines, or social media engagement when the earth is literally tearing itself open beneath your feet. It’s total focus. Pure presence.

Volcano photographers are obsessed not just with the spectacle but with truth. Their images are evidence—of power, change, fragility. They aren’t creating beauty; they’re witnessing it in its most brutal form.

Gear That Laughs at Hell

Regular gear dies instantly near lava. That’s why professionals adapt. Cameras like the Nikon Z8, Canon R5, or Sony Alpha 1 are sealed against dust and heat but still need shade and cooling intervals. Many wrap them in thermal covers or reflective blankets. Some build custom housings out of aluminum or carbon fiber.

Tripods? Usually titanium or steel, because aluminum warps. Drones? Custom-built with reinforced shells and sacrificial propellers. The irony is that no matter how advanced the equipment, nature still wins. Every volcano photographer accepts that their gear is temporary. It’s the cost of entry.

The logistics are just as extreme. Reaching an eruption can mean hiking through toxic ash, hauling 30 kilograms of gear, crossing terrain that melts boots, and setting up camp miles from any form of safety. You don’t “grab a quick shot.” You plan, you survive, you endure.

The Fine Line Between Documentation and Death Wish

When the eruption starts, adrenaline replaces reason. The sound is overwhelming—a roar that feels like the sky is splitting open. The air is hot enough to scorch your lungs. You can’t stand too close, but you can’t look away either.

Some photographers get carried away—literally. Over the years, multiple professionals have died chasing eruptions, either from gas exposure, falls, or sudden lava surges. Their deaths are rarely publicized, but within the community, they’re remembered as a brutal reminder that the line between dedication and self-destruction is razor-thin.

But those who survive don’t see it as recklessness. They see it as respect. You don’t conquer a volcano—you negotiate with it. Every shot is borrowed time.

The Image That Outlives the Risk

Why do it? Why risk everything for one photo? Because when it works, the image outlasts the fear. The best volcano photographs aren’t about lava—they’re about awe. They remind us that the planet is alive, volatile, and indifferent to us.

Look at the work of photographers like Ulla Lohmann, Carsten Peter, or Kōichirō Itō. Their images are both terrifying and transcendent. They’re not showing destruction; they’re showing birth. Lava isn’t just fire—it’s the earth reinventing itself. To capture that moment is to document creation itself.

These photos make you feel something that modern photography often forgets: humility. In a world of filters and performative “wanderlust,” volcano photography is too raw to fake. You can’t stage it, can’t retouch it, can’t replicate it. The volcano either gives you the shot—or takes it away.

What It Teaches the Rest of Us

Even if you’ll never step near an active volcano, there’s something to learn from those who do. They embody the essence of photography: commitment, patience, and respect for reality.

Volcano photographers remind us that true art demands risk—not necessarily physical, but creative, emotional, professional. They remind us that photography isn’t about trends or aesthetics; it’s about capturing what can’t be repeated.

Every image they take exists on borrowed time, forged between danger and awe. And maybe that’s the point. Photography, at its core, is about freezing something that’s about to disappear. Few things disappear faster than lava.

Final Word

The dark truth of volcano photography isn’t just the danger—it’s the obsession. These photographers don’t flirt with death for thrill; they do it because no other subject matches this raw collision of beauty and violence.

Their cameras melt, their bodies ache, and their lungs sting-but the resulting images are eternal. They remind us that photography began as documentation of life itself, not as a way to build an audience.

Chasing lava isn’t about fire-it’s about reverence. It’s the last place where photography still feels ancient, holy, and human.